A Malickian period piece and so-so Dramatic Competition entries round out Sundance 2025

Our final Sundance 2025 dispatch highlights Train Dreams and Dramatic Competition films Twinless, Bunnylovr, Ricky, and Plainclothes.

My final dispatch for Sundance 2025 is bolstered by finally having access to a large swath of films from the festival that were only made available for folks covering it remotely on Wednesday. Among those films were most of the U.S. Dramatic Competition lineup. Of that selection, the lovely anthology Sunfish (& Other Stories On Green Lake) made my list of most anticipated movies for the fest, while I noted that the ho-hum romance Love, Brooklyn coasts by on its talented cast in my last write-up. Many of the other films in this section err towards the latter, but going through all the new movies at my disposal uncovered one gem that cinephiles should be looking forward to for the rest of the year.

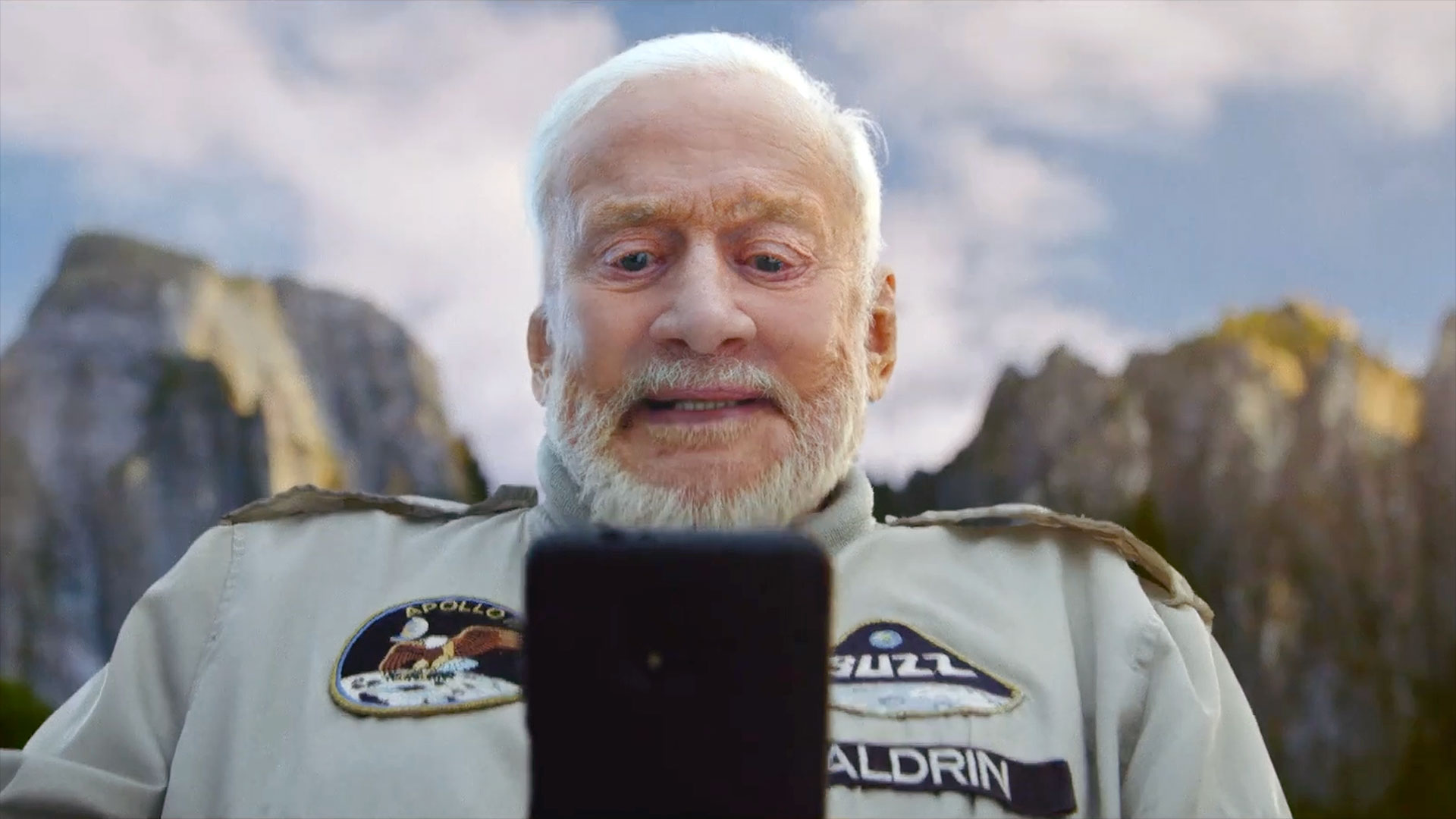

Train Dreams (B+), a Premiere rather than a film vying for a Dramatic prize like the rest in this dispatch, marks a big step forward for filmmaker Clint Bentley. Bentley last directed the endearing but formulaic character study Jockey, which gave standout character actor Clifton Collins Jr. his due at Sundance in 2021, and recently earned an Oscar nomination for co-writing the prison drama Sing Sing. Train Dreams is a different animal than both, a thoroughly engrossing period piece of dreamy details. Adapted from Denis Johnson’s novella, the story of one man’s lifetime—ranging an absurd technological expanse, from constructing the railroads of the West to witnessing televised spaceflight—is quietly told, in conversation with Kelly Reichardt and Terrence Malick.

Train Dreams was recently picked up by Netflix, but it deserves a big-screen release. The leap that life takes a simple logger (Joel Edgerton) over the course of a single generation stands in for that inevitable left-behind feeling that creeps up with age, here inspiring awe rather than pissy fist-shaking at the changing times. The whole film is awestruck, this potentially cloying tone justified by a devotion to golden hour nature photography, candlelight and campfires, and production design (courtesy of After Yang’s Alexandra Schaller) that transports you as deeply as the untamed forests. Edgerton’s soft-spoken woodsman embodies this observational perspective, though wry voiceover and some choice bit players (William H. Macy steals the show as the incredibly named Arn Peeples) add a bit more edge to the affair.

As he works the land and loves his family (Felicity Jones winningly plays his wife), the world turns, its cruelties and inspirations raining down in equal measure. It’s a film that filters a familiar sensation—that as soon as you finally get comfortable doing something, it’s obsolete or not long for this world—through a detailed time period and profession. Its protagonist isn’t just haunted by universal regrets, wishing for more time with his loved ones, but by the pointed cruelties of his era. Train Dreams is about things coming to an end just as you finally start figuring them out, and how that lamentable phenomenon affects not just individuals, but nations and cultures. And, just as the grasses begin poking through the ashes of a forest fire, the ones coming after us have nothing else to do but start the cycle over again.

Focused on the vicious cycle of imprisonment, parole, and reoffence, Ricky (C) inelegantly makes its case about the struggles of a recently released 30-year-old. Rashad Frett’s jittery feature debut is ironically more intent on punishing Ricky (Stephan James) than giving him a chance. Rather than understanding the stunted man at its center—having been locked up for 15 years, half his life was spent in jail—or those around him (mostly one-note women), the frantic handheld camera is dead-set on James’ physical tics of discomfort or the plot machinations that conspire against him.

Frett and co-writer Lin Que Ayoung plant the realistic seeds of post-incarceration life as an impractical series of bureaucratic nightmares, but can’t resist throwing some juicier (and more illogical) dramatic turns at their central character. Ricky, a man left behind by technology, by puberty, by his family, by his community, has plenty of built-in problems the film merely nods to. Rather than investing in these small, mounting obstacles and the domino effect they have on a life that must be lived according to strict rules set by an uncaring system, Ricky introduces big blowups followed by bigger monologues. It’s a blunt approach for a film that’s best when investing in the day-to-day textures and pain points experienced by someone in Ricky’s shoes.

On the other side of the law (kind of) is Plainclothes (C), which sees Tom Blyth play an undercover cop whose job somehow consists entirely of entrapping men cruising for sex at a ‘90s New York mall. When he falls for one of his would-be victims (Russell Tovey), the film becomes a gay tragedy brought to its knees by writer-director Carmen Emmi’s unrelenting stylistic futzing. Neither Blyth nor Tovey (both Englishmen) look or sound like they fit into the well-constructed period setting, but this is overwhelmed by Plainclothes’ formal aesthetic.

The editing is constantly in motion. The film utilizes format changes for things like memories—like grainy home movies—and when Blyth’s POV goes into predatory police officer mode—taking on a zoomed, security cam-like view. Aspect ratios bounce back and forth incessantly. In moderation or with a strict level of control, these factors could enhance (or at least reflect) the closeted cop’s compartmentalized perspective. Instead, as the film develops from an icky “homophobic cops are probably just queer” shorthand to a more nuanced and upsetting place, these stylistic choices take you out of the anxious headspace rather than imprisoning you inside it.

As the film moves back in forth in time and location—the latter seesawing between the pair’s discreet hookups and the cop’s jam-packed, Christmas Eve In Miller's Point-style family gatherings (Maria Dizzia also stars in this one as a harried mom)—it muddles its lead’s painful trajectory and how damaging it’s been to conceal this part of him. Blyth sometimes goes as broad as the rest of the film to convey this eroding ache, but Tovey (playing a more seasoned closeted man) is often stunning as his self-protective foil.

Foils abound in James Sweeney’s ridiculous Twinless (B-), where dark comedy springs up from the death of an identical twin. An excellent Dylan O'Brien plays a dual role as gay hotshot Rocky and straight dimwit Roman…at least, he does until Rocky gets plastered by a passing truck. At a support group for those who’ve lost twins, Roman meets Denis (Sweeney), who reminds him of his brother and offers him a surrogate second half that he’s adrift without. A few twists and turns later, and Twinless becomes catty gay erotica just clever enough to pull off its sillier ideas.

O’Brien is the real selling point of the charming low-key film, his understated turn as Roman balancing out his scenery-gobbling costars and providing some gut-laughs as an oblivious schlub. As writer-director, Sweeney injects his sophomore effort with some amusing visual gags, coordinated costumes, and a look that’s far more thoughtful than your run-of-the-mill comedy, not to mention a handful of good punchlines. As an actor, though, he can seem a little lost when not delivering snippy zingers or long writerly monologues. Surrounding himself with O’Brien and Aisling Franciosi (endearingly cheery) only emphasizes the difference during the film’s more earnest moments. But Twinless does have a heart underneath its zany concept. That emotional core powers its Cut-cover-story-like confidence, which watches one bad choice snowball catastrophically and absurdly through several half-lived lives.

Bunnylovr (C-) is another film from a writer-director-star, watching off-handedly as Katarina Zhu plays a cam girl aimlessly dinking around New York. Zhu’s dreary drama contains plenty of specific screenplay threads, ranging from the idiosyncratic (a creepy client sends her a rabbit to care for, then torture) to the painfully generic (an estranged dying dad; an annoying friend played, per the New York Indie Film Mandate, by Rachel Sennott). All of them, though, are basically ignored in favor of the dullest version of big-city ennui.

With half-assed symbolism and an attention span too short to actually examine any of its topics—including the mundane realities of sex work—Bunnylovr’s narrative episodes blur into a familiar haze. Zhu never finds much of a character to play, nor much of a world for that character to live in, but those rare moments that actually do feel real, like a crowded mass of Chinatown gamblers, offer a flash of color amid the tedium.

![[DEALS] iScanner App: Lifetime Subscription (79% off) & Other Deals Up To 98% Off – Offers End Soon!](https://www.javacodegeeks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/jcg-logo.jpg)